No Ghosts Need Apply: BBC Sherlock's "The Abominable Bride"

/It is a fairly widely known fact that I will watch practically anything relevant to Sherlock Holmes and walk away happier than I was previously, always excepting Rupert Everett and his pair of execrably brooding eyebrows in “The Case of the Silk Stocking.” (Each of them, both singly and at times even in concert, gave me cause for profound grief in that god-awful film.) So when I get served the heady talent mishmash of Benedict “High-Octane Hamlet” Cumberbatch and Martin “My Face Does Pony Tricks Ponies Never Dreamed Of” Freeman, not to mention a stellar supporting cast and a concept created by unrepentant card-carrying Doyle fanboys Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, I’m confident I’ll gobble the dish down. This doesn’t by any means indicate there aren’t vast quality inconsistencies from episode to episode of the justly acclaimed BBC Sherlock series, however, even internally within each installment, and “The Abominable Bride” turns out to be no exception, though when taken altogether a rip-roaring Victorian romp likely destined to please more viewers than it dismays.

Remember when Mofftiss (so dubbed by the internet fandom) delivered a perfectly paced action thriller rife with genuinely clever deductions and thrilling escapes in “The Great Game”? So do I. Remember when the entire plot of “The Empty Hearse” was predicated on a train that disappeared mysteriously in a tunnel where there were no other tracks for it to turn onto, but really in the big reveal, actually we come to find out that there definitely were other tracks for it to turn onto, et voila, the mystery is solved? I remember that too. (And don't even get me started on "The Blind Banker.") “The Abominable Bride” is neither as exceptional in plotting as their best work, nor quite a “whoops, we found more train tracks” sneeze of a story, but ultimately nothing whatsoever to do with the plot matters in the slightest degree, for reasons I shall get into presently.

The prospect of watching Freeman and Cumberbatch’s dynamic duo trade their quips and conduct their no-look passes (it’s a walking stick this time instead of a pen) within the time period of the original Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was droll for about a dozen reasons before fans ever so much as saw a clip of the footage or posted a selfie on the set lot. The BBC series is an exceptionally lovingly rendered modern portrait of a timeless hero and his equally stalwart and no less immortal best friend, and more or less all the nerds in the yard were ready to watch them hailing hansom cabs and navigating gaslit streets the way they did in the literary classics. To boot, in an aspect that's amusing to some and grating to others, BBC Sherlock is hyper-aware of itself as a fannish adaptation, and for anyone who feels as if they are drowning in meta when watching it, I always feel I must point out that Doyle paved the way for this to happen with every stone he planted. Canonically, Sherlock Holmes is not only aware of himself being in the Strand Magazine; his fame grows exponentially because of the publicity in real time, thanks to the real publication, and he chides Watson over his fictional stylistic endeavors, which are actually Doyle's real achievements—the only way the BBC series could possibly be as meta as the originals is if Cumberbatch were making commentary about appearing on BBC One every other year, which he doesn’t. “The Abominable Bride” is not a stand-alone and does not work outside the context of the entire arc of the show—but it is a remarkably well-shot and produced Gothic ghost story, for the most part, and its nods and winks serve the modern day London its writers have imagined, and thus truly needn’t be criticized as a self-indulgent nostalgic set piece.

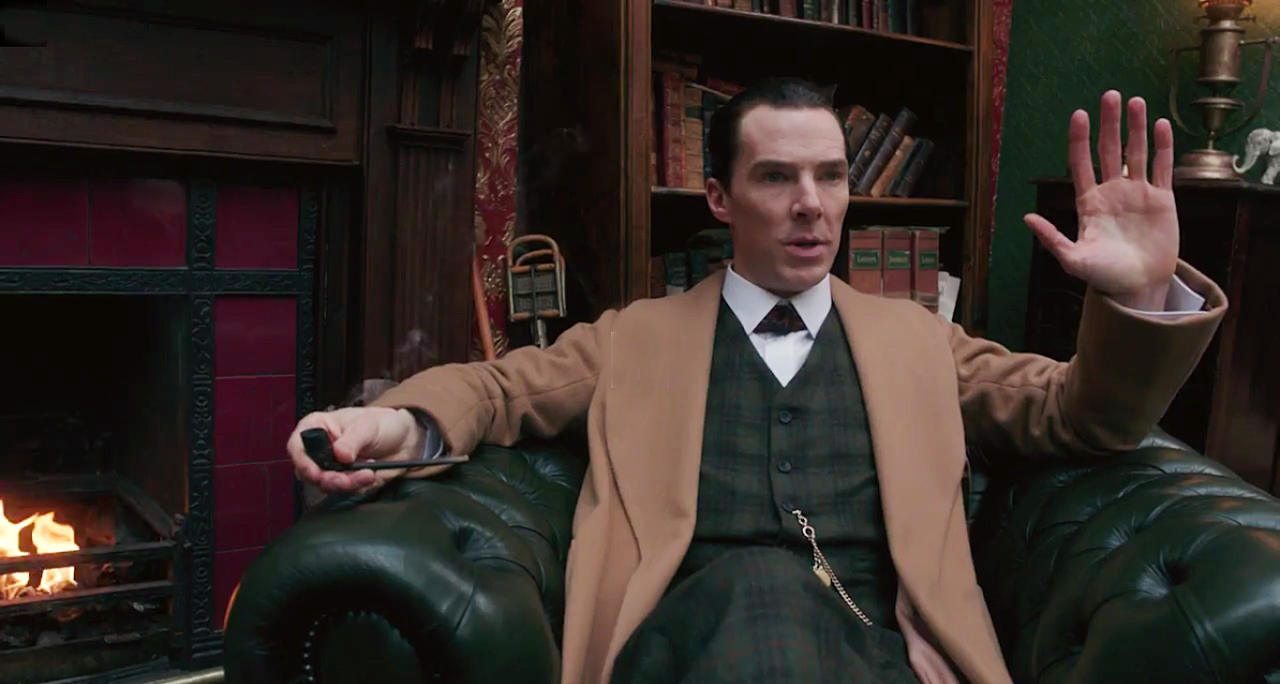

Spoilers below the pretty pretty picture…

To the plot's best points first: it is enormously atmospheric in all the right M. R. James, Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, and yes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle fashions, and drops so many Easter eggs in the lap of the canny viewer that one walks away with a veritable pastel bucketful. Emilia Ricoletti (a reference to the unwritten case “Ricoletti of the club foot and his abominable wife”) has been killing people—mainly herself, and afterwards her husband, which Rupert Graves’s always excellent Inspector Lestrade insists is in quite the wrong order entirely. As a matter of fact, reports of her murder spree—always of men who have in some way transgressed—continues long after her corpse is in the ground. Meanwhile, Sir Eustace (a bully and an abuser and a character from “The Abbey Grange”) is being threatened by a terrifying unknown assailant who sends him five orange pips (from the story of the same title), and this shadowy enemy turns out also to be the deceased Emilia Ricoletti, except it can’t be Emilia Ricoletti, because she is, of course, dead as a doornail (with ultimate repercussions reminiscent of “Lady Frances Carfax" and a rather nice "The Speckled Band" stakeout). Add to this mix verbatim passages from A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of Four, “The Greek Interpreter,” “The Creeping Man,” “The Second Stain,” and “The Final Problem,” to name a few before I dizzy myself, and you basically have the canon dropped into a blender and reconstituted with a very nice set and costumes.

Is it confusing? You bet. Why is it confusing? We're getting there.

To the worst aspect of the plot next: unfortunately, Emilia Ricoletti turns out to have been a martyr for the cause of female rights, and is really an entire movement of women disguised as Miss Havisham, because as everyone knows, feminism is about slaying that man what done you wrong. Feminists also are known to meet in de-sanctified chapels chanting Latin in a chic basic black dress version of the KKK uniform, another direct nod to “The Five Orange Pips,” because really we are less about equality and votes and more about forming a bloodthirsty gang with a savage ghost as a mascot to cover up our murder sprees (amIrite, ladies?). As a final nail in the coffin that intended to be a feminist text, the women’s rights speech is delivered not by Dr. Molly Hooper, an excellent side character (played by feminist Louise Brealey) who is forced to cross-dress to work in the mortuary, nor by Mrs. Mary Watson (played by the equally strong Amanda Abbington), who solves the crime before Holmes can, but by Holmes himself, as he stands there defending a death cult with a fetish for hoods. They are “a legend to strike terror into any man with malicious intent,” and were roundly not congratulated for this on Twitter, Reddit, tumblr, and other forums where women grow irritable when their historic trailblazers are compared to the KKK. Once again, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s females turn out to make better points and provide more truly feminist arguments despite having been written some little time ago than the BBC’s, as witness Irene Adler, Lady Brackenstall, Violet Smith, Violet Hunter, and Lady Hilda Trelawney Hope to name a few.

Hi-five, Arthur. You still got it, bro.

None of that actually matters, of course, though (or so we are meant to believe), because none of that is the real plot. If that were the real plot, we'd want an explanation for why in the name of god Holmes locks his terrified client indoors with the one woman he thinks has a proper motive to kill him, etc, etc, blah blah blah. You want an actual plot? Chill out with a whiskey and maybe a marijuana cigarette, we're getting to it.

There are those who were looking forward very much to “The Abominable Bride” being an all-Victorian piece of separate theatre awash in misty grey tones with yellow lanterns beaming hazily into the fog, and were unhappily surprised at the revelation that all this Victorian running about in cape-backed greatcoats was due to a drug-induced fever dream in the Mind Palace of the Sherlock Holmes who was exiled at the beginning of “His Last Vow” and boarding a flight to his certain death. Multiple people expressed dismay and confusion over the blending of the two worlds, but I hereby make my case for it: since the very first episode, “A Study in Pink,” BBC Sherlock has unabashedly been about Sherlock Holmes—not the cases, but the person, and the relationships he forges, particularly with his flatmate and blogger John Watson. If what you wanted was the purity of an idealized 1895 without any cell phones or cars or jet planes (or people of color, or desperate poverty, come to that), you were roundly disappointed; if, however, what you wanted was genuine character development of Cumberbatch’s uniquely fragile and formidable Sherlock, why then you got it in spades.

Sherlock has not been himself since his own faked death, Jim Moriarty’s real death, John’s marriage, and their subsequent war with Charles Augustus Magnussen. He fell off the wagon rather spectacularly in a “The Man with the Twisted Lip” nod in “His Last Vow,” and the canon for the show just got a whole hell of a lot darker, dark on a par with Rupert Everett’s eyebrows but with a metric asston of genuine feeling, which Rupert Everett’s eyebrows (both the right and the left) entirely lack. Example: it is now taken as given that after serving a week in solitary confinement for his own protection after murdering Magnussen to save John and Mary, Sherlock went far enough down the rabbit hole that when he was sentenced to lonely exile on a suicide mission not expected to outlast six months, he decided to procure the Long Island Iced Tea of drug cocktails, say goodbye to John Watson, and then board a plane to his death with tears in his eyes, having already taken enough chemicals to overdose while reading John’s blog entry regarding the day they first met. (I am not making this up—the show writers made it up.) Anyone explaining this away (as they both attempt and fail to do in the episode) with “Sherlock did the drugs to solve the case of Emilia Ricoletti in his Mind Palace to solve the case of Moriarty’s return” ought to be reminded that Sherlock had no idea Moriarty had ostensibly returned before his plane landed. We are talking deadly levels of pain here, my friends, and it only gets worse.

Adding eight hundred thousand more kilograms of angst to this black hole, we have Mark Gatiss’s show-stealing turn as Mycroft Holmes, Britain’s most distant, smug, and ultimately loving big brother. Smile when the Doylean version of Mycroft is all but lampooned in Sherlock’s Mind Palace, as the appropriately obese Mycroft takes bets on how long he’s likely to live if he eats another plum pudding. Tear up as Mycroft blames himself for Sherlock’s relapse into drug abuse, suggesting he should have anticipated that being alone in a jail cell would be literally locking Sherlock up with his own worst enemy. Weep quietly at a flashback to the young brothers as Mycroft retrieves his sibling from a filthy drug den, and we learn of the agreement that Sherlock always makes a list of precisely what poisons he took so that Mycroft can save him, time after harrowing time. Bawl your eyes out a little more at Mycroft’s vow always to be there for him and his almost pleading appeal to John to look out for his delicate magic crystal unicorn of a baby brother.

Long story short: "The Abominable Bride" was a flawed episode of a flawed show, but it was also an excellent episode of one of the best Sherlock Holmes adaptations made in the last fifty years, one I rank with the Granada series among personal favorites anyhow, and while my inner monologue was "kill it with fire" when the KKK outfits surfaced, other aspects greatly endeared me to the narrative despite its (in my opinion deliberate) confusion and disorienting switches between Now and Then. Is it a cop-out to not bother with a solid plot because "it was all in Sherlock's high-as-Keith-Richards mind"? Probably. Were the writers trying to talk about something other than the cases? In my opinion, absolutely.

Because "The Abominable Bride" ultimately isn't even about Sherlock Holmes--it's about Sherlockians.

Bear with me here. The concept of Sherlock’s Mind Palace as an excuse to write a Victorian episode was admirably done, in my opinion, but it goes beyond character development into something more timeless, for all that the development is profound. Sherlock’s doubt and deep-seated self-loathing are still characterized by Jim Moriarty in the Victorian world, for example, and even in his mind he cannot bring himself to discuss having faked his own death with imaginary John, despite having begged forgiveness for the deception. But when we reach Reichenbach Falls—the real Reichenbach, the waterfall, the one from the stories we love so—“The Abominable Bride” becomes something else entirely, a Joseph Campbell-esque tribute to the character who has died so many times, and risen from the dead just as frequently in countless adaptations. It becomes about the audience, about the people who love these flawed champions of right. “There are always two of us,” John says when he appears (un-canonically) at the Falls to save Sherlock Holmes from Professor Moriarty (metaphorically Holmes himself), and yes, it is possibly the most meta line in the program, but it is also the truest. For as Vincent Starrett once put it so perfectly, “Only the things the heart believes are true,” and all other matters—plots, clues, modernity vs. nostalgia, what have you—are secondary to the friendship that has inspired millions of people worldwide, people who believe that time period makes no difference regarding its always being 1895.